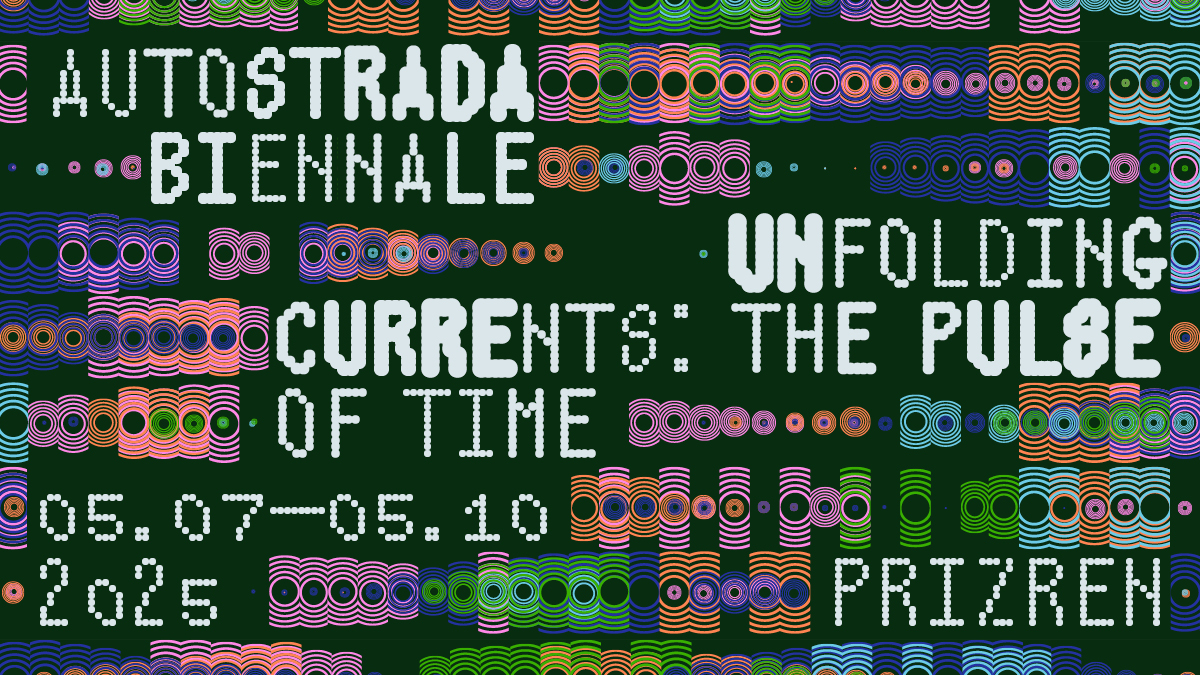

The 5th edition of Autostrada Biennale, “Unfolding Currents: The Pulse of Time,” curated by Erzen Shkololli, July 5 to October 5, 2025

“Unfolding Currents: The Pulse of Time” highlights the dynamic interplay between artists, artworks, audiences, and the rich historical context of Prizren, Kosovo. A city layered with architectural and cultural history, Prizren serves as a living repository of the country’s heritage.

In its tenth year, Autostrada Biennale adopts a situated approach, inviting artists from various generations and geographies to engage deeply with a number of the city’s historical sites. By reimagining past works and commissioning new projects, this edition fosters a vibrant dialogue in the present while critically reflecting on the past.

“Unfolding Currents: The Pulse of Time” embodies the spirit of this dialogue. The phrase “Unfolding Currents” evokes the continuous evolution of historical and artistic narratives, while “The Pulse of Time” captures the rhythmic, persistent nature of these transformations. This title emphasizes the biennale’s active engagement with the layered contemporary moment we inhabit.

Situated along the Prizren River, the city of Prizren is composed of many pasts and presents. Formed over millennia by a retreating glacier, Prizren, now the second-largest city in Kosovo, lies at the foothills of the Sharr Mountains. Bronze Age fragments have been uncovered around the city’s historical fortress. Byzantine churches sit alongside significant Ottoman mosques and residences. Many examples of Yugoslav infrastructure remain in use, while evidence of the Kosovo War leaves no surface unmarked.

The exhibition unfolds across several historical sites, from the Clock Tower and Shani Efendi House to Gazi Mehmed Pasha Hammam and beyond. Many of the featured projects are already taking shape. This announcement invites readers and future visitors on a journey through key sites where they can encounter these projects in formation.

The Clock Tower and Hamam of Shemsedin Ahmet Bey are key landmarks in Prizren. Built in 1498, the hamam ceased functioning by the mid-19th century when the Clock Tower replaced part of its structure. Originally wooden, the tower was later rebuilt in stone by Eshref Pasha Rrotulli. Its clock and bell, removed in 1912, remain missing. After years of neglect, restoration efforts in the 1970s transformed the hamam into the Archaeological Museum of Prizren, showcasing artifacts from the Neolithic to the Ottoman period.

For this year’s biennale, Vadim Fishkin’s Lighthouse (1996) transforms the tower into a living signal. Pulsing lights, linked in real time to the artist’s heartbeat wherever he is are transmitted via mobile technology. Having traveled to various contexts, the work now turns the site into a beacon, guiding the way on the biennale journey.

A short walk from Prizren’s central marketplace, Shani Efendi House continues this exploration of embodied practice. Built in the 1930s as a residence, it later became a space for political and social gatherings during the Yugoslav period.

Inside, the mixed-media paintings and sculptures of Prizren-born Simon Shiroka deepen the exhibition’s connection to local artisanal practices and mythologies. Steeped in the city’s history of craft, Shiroka’s work brings together traditional approaches to silversmithing with contemporary art by rendering intricate scenes based on dreams, complex filigree elements, Kosovar symbology, and more.

Meanwhile, Robert Gabris’s large-scale drawing The Garden of Catastrophy (2024) seeks, in his words, not to “aestheticize the concept of dying ”¹ but to work with flaw, failure, and imminent disaster. Gabris’s intricate pencil lines, depicting interrelated beings, are “an integral part of retelling historical oppression and pain, embodying the idea of existence afterward. ”²

Amplifying this atmosphere, Anita Muçolli’s ceramic interventions reference Kosovar fables, family stories, and childhood memories. Her slick, dark-patina forms fill the space—evoking horror-genre depictions of the monstrous and reminding viewers that human animals are not the only inhabitants of this space.

Around the corner is Gazi Mehmed Pasha Hammam. Built in the 1570s, the architecture features twenty domes and is one of the biggest hammams in the Balkans. The site was partially restored in the 1970s but then abandoned. In the last fifteen years, restoration efforts have restarted, allowing for limited use of the building for cultural and educational purposes. As of 2024, phase one of the hammam’s refurbishment has been completed, creating access to major sections. It is within this regenerated structure that Doruntina Kastrati will respond. Often taking sculptural, infrastructural, and filmic forms, Kastrati’s work brings to the fore fragmented bodies, labor conditions, and various aspects of precarious life. At the start of this new chapter for the hammam, Kastrati initiates an important artistic dialogue with the space.

A short walk further, Dorambari Family House, opened to the public for the first time, offers an intimate domestic setting of Ottoman-era flourishes in which to view artworks. Here, the warm wooden interiors of this historical residence brings visitors into close proximity with a number of works that activate multiple senses. Laurent Mareschal’s Beiti (2011)—meaning “my house” in Arabic—is a large-scale installation of mosaic tiles made of aromatic spices central to Palestinian and other Middle Eastern culinary traditions. These fragrant elements fade over time, tugging at memories in ways that are hard to articulate, while also reminding visitors of the devastation of many cultural practices in the Middle East.

Around the corner from these affective odors a knocking can be heard. Emerging from behind a door, Nika Špan’s work Who is there? | Who’s there? (2010), asks the viewer to become a listener—and a participant too, if they choose to respond to the work’s central questions. Also moving through the house, Edin Zenun’s ‘small format paintings are reminiscent of gestural choreographies. “³ The serial works in their ‘fragile looking, self-produced frames’ create a ‘predetermined score which the viewer’s eyes reenact as each composition offers a kind of explanation for the next. “⁴

This exploration of embodied practice continues inside the house with David Fesl’s archive of palm-sized object assemblages. The intimate and surprising compositions of everyday elements resist easy interpretation. ‘Rather than supporting the meanings of objects, [Fesl] removes or redirects them…the intermingling of findings creates a new form of family or kinship. “⁵

Autostrada Hangars are the next stop in the biennale route, at what was the periphery of the city, and today is Prizren’s Innovation and Training Park. The site has a complex military history extending back hundreds of years. More recently, in the early 1900s, it was used by Ottoman Empire soldiers as a camp, after which the site housed Yugoslav military personnel. From the late 1990s, after the Kosovo War, it became a base for the German Bundeswehr until Kosovar independence in 2008, at which point it was gradually demilitarized. Now a growing hub for innovation and business, two of the monumental hangars here are home to Autostrada’s year-round program of exhibitions, events, and residencies.

For “Unfolding Currents: The Pulse of Time” these structures are inhabited by projects such as Tamara Grčić’s expansive field of glass bottles entitled Lichtgrün, grün, feuille-morte (2004). The work spills across the space, moving in waves of green and changing with the light of day as the artist reflects on industrialized production and flows of consumption. Materials circulate within and across borders, while language and meaning change with shifting contexts. The work by Nathan Coley is drawn from graffito he witnessed in Jerusalem: I Don’t Have Another Land (2022). Aware of the complex nature of where his pieces are situated, Coley is interested in the power of language in the minds of readers, with all the values and beliefs they use to interpret the words he brings to light.

It’s a more shadowy underworld where Brilant Milazimi’s paintings dwell, claiming space for meditations on memory, trauma, hope, and freedom. The Prishtina-based artist’s work features toothy tentacular connections and surreal creatures. Milazimi’s symbologies hazily gesture toward tensions underlying everyday experiences.

In the months ahead, the biennale will also engage artists Blerta Hashani, Armend Nimani, Stephanie Rizaj, Lois Weinberger, and many more.

An accompanying public program, focused on notions of place and collective experience, runs throughout the biennale. Tao G. Vrhovec Sambolec’s work punctuates the program, with Tuning In – the neighborhood (2019), a sound event that invites musicians at the Lorenc Antoni Music School, residents of the Marin Barleti Street around it, and the wider Prizren community to attune to the single note “a” as well as to one another. This ritual of listening, synchronization, and performing together challenges conceptions of public space and activates the city, along with the exhibition works.

Through limited activations of live works such as Sambolec’s, residents, as well as those from further afield, are invited to experience artistic questions and creative processes in real time rather than through documentation. This comes back to this biennale’s insistence on presence. The fear of not being present is often behind the need to document.

As the curator of the 5th edition of the Autostrada Biennale, “Unfolding Currents: The Pulse of Time,” I am honored to lead this edition. As a curator from Kosovo, I have a deep understanding of the groundedness and fragility of artistic practice here.

The temporary nature of the artworks in “Unfolding Currents: The Pulse of Time” means that many aspects of their vibrant questions and proposals will inevitably fade. Despite this, these projects are designed to leave a lasting impression on both our memories and the city’s fabric. The legacy of previous biennale editions, seen in the work of Open Group, Neda Saeedi, and Alban Muja, highlights how these artistic contributions continue to evolve and resonate.

The history of Prizren, marked by memory, erasure, and trauma, shapes our approach and reflects the resilience of Kosovar culture. This edition seeks to honor and build upon this legacy by exploring new ways to engage with and preserve our heritage spaces. The Autostrada archive—which is expanding in parallel to this biennale—serves as an important repository for artist publications, biennale materials, and evolving insights. My hope is that “Unfolding Currents: The Pulse of Time” will foster meaningful dialogue and reflection for artists and audiences alike, both now and in the future.

_

¹ Robert Gabris, “The Garden Of Catastrophy”, 2024. Online: https://robertgabris.com/the-garden-of-catastrophy.html.

² Ibid.

³ Vanessa Joan Müller on the work of Edin Zenun in Unknown Familiars, eds.Philippe Batka, Vanessa Joan Müller, Vienna: Leopold Museum, 2024.

⁴ Ibid.

⁵ Excerpt from a text by the artist and Zuzana Blochová in I will watch with you, David Fesl, Esther Kläs, Prague: Cursor Gallery, 2024.